This dissertation is based on a lifelong interest in aesthetics and the visual arts. I regularly organise art exhibitions for the abstract painter Ian Reddie. Digitising his work and developing a website made me think about the challenges and opportunities for curating art on-line.

I am also interested in graffiti, which I have recorded over several years locally and internationally. In a city landscape, graffiti can be an expression of individualism and an integral part of urban graphics and signifiers, complementing billboards, neon signs, multi or giant flat screen displays. These corporate and commercial installations are in contrast to the spray painted or stencilled graffiti, portraying intriguing singular expressions found amongst the concrete jungle. Due to graffiti’s effaceable or clandestine nature, the works are usually of an ephemeral quality, offering a unique one-off viewing rooted in a particular time and location. Re-situating graffiti online creates a new virtual landscape juxtaposing the temporality and spatiality of their physical manifestations with their digital counterparts set loose.

I am also interested in graffiti, which I have recorded over several years locally and internationally. In a city landscape, graffiti can be an expression of individualism and an integral part of urban graphics and signifiers, complementing billboards, neon signs, multi or giant flat screen displays. These corporate and commercial installations are in contrast to the spray painted or stencilled graffiti, portraying intriguing singular expressions found amongst the concrete jungle. Due to graffiti’s effaceable or clandestine nature, the works are usually of an ephemeral quality, offering a unique one-off viewing rooted in a particular time and location. Re-situating graffiti online creates a new virtual landscape juxtaposing the temporality and spatiality of their physical manifestations with their digital counterparts set loose.

Curating

In this dissertation I

often refer to ‘curating’. In an internet context I would like to suggest this

term has a different meaning to the curating of the scholar or art historian. His or her main concern is to present work by an artist or art movement

considered representative within historic presentational conventions (based

on a quote by Teresa Gleadowe, used in Cooke, 2008, p 28). Social media curators borrow from New Media art in supporting a focus from object to process. Process gives artworks time-based, dynamic, interactive,

collaborative, customizable and variable characteristics, in line with a curatorial practice

that resists objectification and challenges traditional notions of the art

object (Paul, 2008). However, unlike New Media art curating, social media

curating does not necessarily involve the active collaboration of the artist, but instead draws on the internet's infrastructure of making art available

anywhere and any time.

‘Les Arts sans frontières’

The Tate Britain symposium in September 2010 brought together a host of academics, curators and technologists to discuss the impact of social media on museum workers and the public. Various speakers highlighted educational and business models illustrating the pressures on the cultural markets driven by a careful juggling act of monetising their art collections and at the same time offering art experiences to the public. One of the keynote speakers, Nancy Proctor, explained that what museums do is ‘collecting, conserving, interpreting and disseminating’ the public good artworks to as wide an audience as possible. The programme of that day which discussed the impact of mobile technologies illustrates that museum walls are no longer the sacred and exclusive space for seeing or indeed ‘consuming’ art, with the interpretations of such activity becoming increasingly malleable and fluid. However, listening to the discussions and watching the presentations of this conference still directed viewers to the same revered institutional spaces albeit accessed online, through official virtual museum doorways.

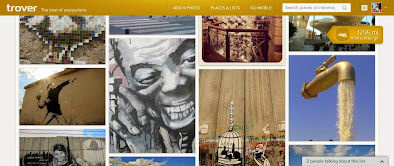

The focus of this project is not museum social or new media policies, which may involve Twitter or Facebook, a virtual tour, augmented reality, or specialised educational apps. The focus is social media gallery spaces that are not administered by museum people. The proliferation of social media apps now encourages all users to curate, share and ‘like’ art. Some of this art may be ‘proper’, collected from online sources, some museum websites. Alternatively users may take their own photographs, legitimately or not, from visiting commercial galleries, locally or on holiday, in public or private spaces. The focus of this discussion is the personal curating which operates outside authorised museum walls. Art captured on smartphone camera and distributed, shared, even edited.

14 Oct 2014

Above: a screenshot of the work available by Mark Rothko, taken from the mobile app ArtStack,

as curated by the ArtStack community.

Other images above:

- Covenant, by Ian Reddie exhibited at the 'Art of Giving', The Royal College of Physicians Hall, Queen Street, Edinburgh 17 and 18 August 2012.

- 'Shark', Underpass located near Bristo Square, Edinburgh, now erased.

- The header is hosted by Thinglink and shows a screen dump taken from Pictfy.

- The image on the left is curated from ArtStack and shows the key points with regards to the social semiotics analysis.