A key observation of this research is the emerging mobility/mooring dialectic underpinning the social media art curating. This is achieved by a set of mobility conditions which I have described as mobility tools and these are featured in the methodological model. This model combined social semiotics with the Mobility literature.

Situated

For all three apps, the emphasis on identifying geographical location is a clear illustration of the mooring/mobility dialectic. The references to the galleries and global pins relate the user and the images to real life locations. The Trover app calculates the relative distance of the user to the photo uploads in miles, (e.g. ‘855 miles from Edinburgh’) displaying icons representing walking, biking or flying. For this app I have also noticed an increase of crowd sourced locations, indicating that the app’s feature also supports its commercial viability. The increased availability of locations from the dropdown menu highlights the shadowing of the app, uploading new locations as these are added by the users.

To reinforce the simulated gallery experience, ArtStack displays the uploaded images similar to a museum display, with the name of artist, title, year, but also any associated analytics such as the number of likes. All the photos however have the potential of being accessed further, given salience by a live url finger icon. Touching the icon acts as entering a 'doorway' into new a gallery space. However, this online experience is driven by a database, reflecting the performance of the artworks in the context of their analytical value.

For all three apps, the emphasis on identifying geographical location is a clear illustration of the mooring/mobility dialectic. The references to the galleries and global pins relate the user and the images to real life locations. The Trover app calculates the relative distance of the user to the photo uploads in miles, (e.g. ‘855 miles from Edinburgh’) displaying icons representing walking, biking or flying. For this app I have also noticed an increase of crowd sourced locations, indicating that the app’s feature also supports its commercial viability. The increased availability of locations from the dropdown menu highlights the shadowing of the app, uploading new locations as these are added by the users.

To reinforce the simulated gallery experience, ArtStack displays the uploaded images similar to a museum display, with the name of artist, title, year, but also any associated analytics such as the number of likes. All the photos however have the potential of being accessed further, given salience by a live url finger icon. Touching the icon acts as entering a 'doorway' into new a gallery space. However, this online experience is driven by a database, reflecting the performance of the artworks in the context of their analytical value.

Pictify has a Museum/Galleries tab which lists a number of

venues, although it is not clear who manages the image uploads, blurring

personal and institutional authorship. For the art curator,

these geographical references may represent a sense of distance and proximity, incorporated into 'the pocket

containers of data, media content, photo archives and secure microworlds'

(Richardon,2007, p 205).

Pictify and ArtStack use a

white background, evoking the contemporary space of the 'White Cube' gallery. Only

ArtStack gives a level of customisation for accessing the artworks, either as a

grouped photo album or by stacking single images in the sequence of uploading,

always evolving depending on the level of user engagement. Simulating

this gallery experience uses a mix of situating and shadowing, whilst the applications

provide a visual log which may be time and/or date stamped

Pictify and ArtStack use a

white background, evoking the contemporary space of the 'White Cube' gallery. Only

ArtStack gives a level of customisation for accessing the artworks, either as a

grouped photo album or by stacking single images in the sequence of uploading,

always evolving depending on the level of user engagement. Simulating

this gallery experience uses a mix of situating and shadowing, whilst the applications

provide a visual log which may be time and/or date stamped

Temporal

ArtStack’s sophisticated trending tool ‘On Show Exhibitions’

filters major exhibition locations, indicating the concurrent effect of

temporality and situatedness. The app lists a fixed-order of locations (London,

New York, Paris, Berlin). Other cities are listed but only visible through

further clicking, indicating a weighted commercial and institutional

trending.

A sense of urgency is being

evoked, with ‘closing soon’ following the same geo-located pattern. Time/space

is neatly pre-assembled allowing users to synchronise calendars and future

plans.

The user is given regular updates of who is engaging when and with what.

Personal messages and status is reconfirmed through delivery of notifications

in the personal mailbox [1] and

pushed onto mobile phone or tablet. It implies that the user may wish to shadow

activities, reciprocating engagement, through liking or following, or, should

the user decide to, add comments to the images.

The user is given regular updates of who is engaging when and with what.

Personal messages and status is reconfirmed through delivery of notifications

in the personal mailbox [1] and

pushed onto mobile phone or tablet. It implies that the user may wish to shadow

activities, reciprocating engagement, through liking or following, or, should

the user decide to, add comments to the images.Shadowing

Pictify takes the analytics-based ‘most popular’ one step further by displaying

the 'most commented' artworks. Here special attention is given for keeping

artworks and users’ comments in a particular grouped (framed) presentation, adding

salience to the 'social'.

In the example of Trover,

popular images are likely to be pushed and featured on various Trover lists.

This favouring is further reinforced through sharing via other social media

sites such as Twitter, Facebook and Pinterest, where the same image or further

assemblages of a popular user/curator may re-appear. Social media application

therefore may curate rhizomatically, in locations of which the user is not

necessarily aware. The curating is persistent, unstoppable, indefinitely, with

the author of the image relinquishing control.

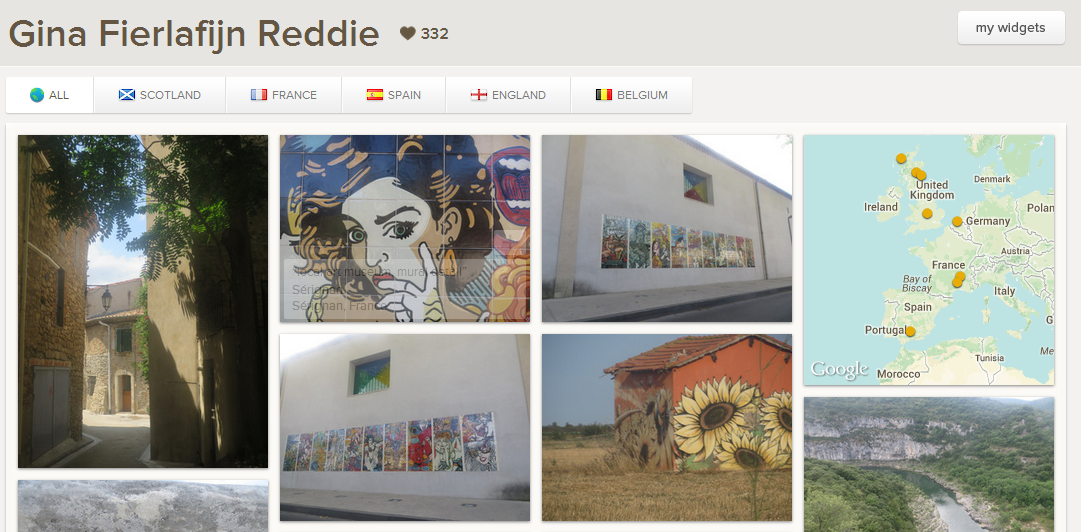

GPS pins on a Google map (with

zoom-functionality) offer Trover users additional shadowing opportunities and

finding relational positions of images to locations. This map feature is

given salience at the top, complete with national flags.

For all three apps, the analytical data displayed at the top of the screen indicate a timely update on the reciprocating users and associated uploads. Trover and ArtStack both make use of a status number displayed in bright red. This neat and simple feature is a way of checking who is checking who and indicating how images may have been appropriated by other users, uploaded onto other users’ personalised spaces.

Summary

Büscher et al

(2011a) suggest a mobility method which tracks and

simulates, mimics and shadows people, images and information. Social media app and smartphones have such affordance,

allowing users to explore the aesthetics of urban and virtual landscapes.

The

applications employ a number of mobility tools which in the project have been

identified as conditions of the ‘temporal, shadowed and

situated’. These characteristics underpin the mobility/mooring dialectic. Artworks

and graffiti may appear on various social media sites, curated and re-curated,

and this has been can be described as rhizomatically. There is no limit to how often

artworks appear, indeed Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of multiplicity can be

used to describe the social media curatorial flow. Mobility conditions are the

result of the socio-technical conditions that are connecting people and spaces,

and the information that flows across the material and immaterial

infrastructures.

For the mobile curator, the

position of being present on an app and using the mobility conditions of

temporal, situated and shadowed may offer a sense of being in the constant

centre and constantly being de-located. This may represent a paradoxical

situation, whereby users and their artefacts become ‘geographical

representations of actual situations [that] are recorded while being experienced

so that life-world becomes a representational artefact and movement becomes

visual output’ (Adami and Kress, 2011, p.192).

This experience may be

considered part of a performative experience which is being discussed in the

next section.

[1] To

give an indication, to date (22 August 2014) I have received 400+ messages from

ArtStack indicating user activity with uploaded artefacts or artefacts I have

engaged with. For Trover I have received around 100 'thank you's', although some of

these messages refer to multiple engagements and so the number is much higher.